In 2012, Alex Ketley identified a pattern in his work as a dancer and choreographer: he had worked almost exclusively in urban centers and performed for city-based audiences – most of whom were already accustomed to modern dance.

“It was almost like preaching to the choir,” Ketley mused.

Creating work for like-minded patrons in art-saturated cities left Ketley, a lecturer of ballet and choreography in Stanford’s Department of Theater and Performance Studies (TAPS), longing for work beyond the walls of studios and concert halls.

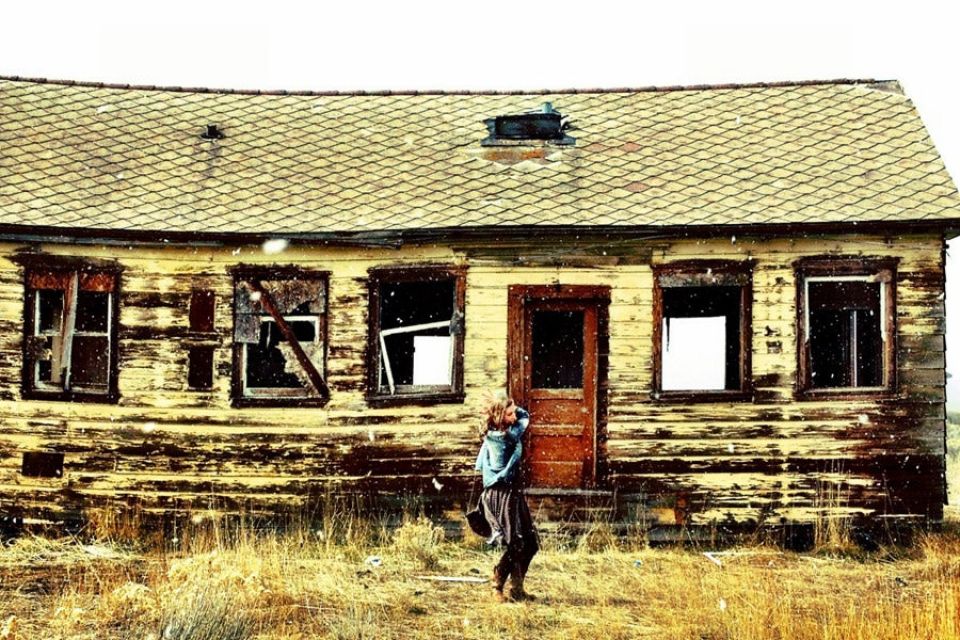

He satisfied that craving through anthropological research throughout the American rural West, where he made conversation with strangers about how dance – in any of its forms – played a role in their lives. Ketley’s experiences are chronicled in his film, No Hero, which will be screened at 8:30 p.m. Thursday through Saturday (May 25-27) at the newly renovated Roble Dance Studio in Roble Gymnasium. The documentary film incorporates live dance – its choreography inspired by the intimate stories Ketley shares on film.

“I felt the way to really challenge myself was to travel extensively throughout rural communities and build a new work in shopping malls, mountains, hotel lobbies, RV parks and the homes of strangers we met,” Ketley said. “I was curious about how, [by] making a work directly in the public eye and engaging people unfamiliar with fine art performance, I could then attempt to truly answer what my role as a dance maker is in society.”

Ketley, a former classical dancer with the San Francisco Ballet and now director of his own dance company, The Foundry, traveled between major cities as though there were “vast art deserts throughout the country.” While exploring the rural West, however, his experiences contradicted many popular assumptions.

Most significantly, he discovered that art – specifically dance – was not absent in rural America. Dance played critical roles in individual lives and communities, just as it did in the urban art centers. Ketley found dancers in cowboys and elderly widows and in bingo halls.

“The differences between us were put on hold while we discussed something inherent to all people: the desire to move, connect and have our stories heard,” Ketley said.

Creating No Hero challenged what Ketley called an “urban/rural prejudice” commonly found in urban environments and even among fellow artists.

“I was with a bunch of choreographers in New York and we were talking about projects we were doing,” recalled Ketley, “and I told everyone I’m going to do this project where I travel throughout rural communities in the West. The response was, ‘You’re going to get killed.’ Of course, that was an exaggeration, but it demonstrated how isolated the field can be at times.”

For dancer Glory Liu, a doctoral candidate in political science who will be performing, No Hero is strikingly relevant to central questions in today’s political climate.

“How do we go about trying to understand the lives and the beliefs of people who are so unlike us?” Liu asked. “What are the ethical implications of characterizing the divide between red and blue states, urban and rural America as an ‘empathy wall’ that has to be breached? What place does dance have in an era when the performing arts have become yet another touchstone of polarization?

“No Hero is an invitation to consider what happens when we shed our expectations of what dance is, who dances, and where dance happens.”

Liu characterized No Hero as part tribute, part inspiration.

“Being a part of No Hero is a tribute to those kinds of stories that often don’t get told in the contemporary dance world,” she said. “But more than that, No Hero reminds me of the possibilities before us if we, collectively, become genuinely open and curious about people, places and dances that we don’t normally encounter.”

Tickets for No Hero range from $5-$15.